Scratch That Itch

It’s not that kind of itch. Get your mind out of that sex-positive gutter.

I have written about my congenital epidermolytic ichthyosis (EI) here: https://medium.com/@teri.adams/im-a-hard-stick-269bdd243319 and here https://medium.com/@teri.adams/everything-old-is-new-again-5273825d89f1, and mention it a lot.

There are many reasons I intentionally talk about my disability so much. It is rare, and people have usually never heard of it. It is my defining characteristic; it has impacted every aspect of my life since I was born.

EI made me “other” in all places: my home and family, my community, my education, medical care, disability status, employment opportunities, social and romantic acceptance, etc. All of it. I was decades into adulthood before Disability Pride was on the public’s radar.

I am going to write about my life and my disability a lot. I want people to have a concrete, plain-spoken example of a person with a disability who is lucky enough to reflect on their experience and be able to write about it.

The Big Itch

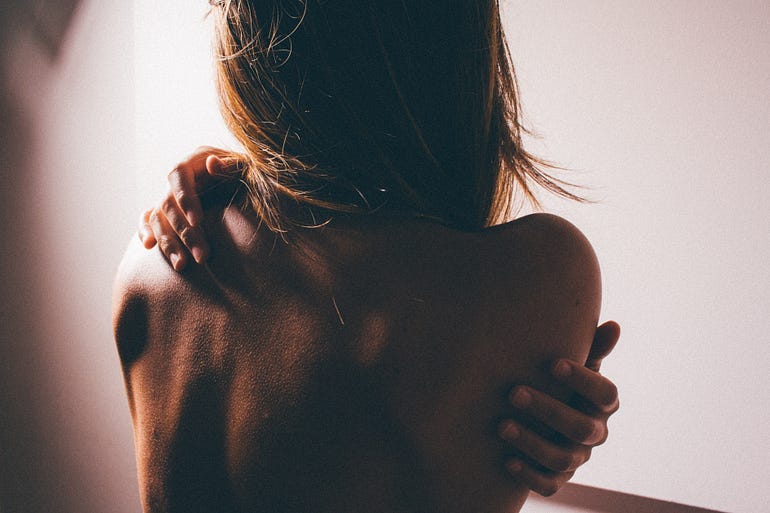

My skin itches all the time in a variety of places. My back pretty much itches constantly. Sometimes, my feet itch so fiercely that I can’t sleep.

When I was little, my maternal grandparents ran an SRO (single-room occupancy) hotel in Portland, Oregon. We would visit several times a year and stay in a big room in the hotel. I slept on an ancient army cot, an air mattress, and a sleeping bag. My cot was by a window with both a pull-down shade and these net curtains. The net curtains fascinated me — they looked like they were crocheted out of a heavy twine or something; I could stick my fingers in the holes and had to be careful not to catch my skin on them. I could see the rooftops of downtown buildings and hear cars on the street, a different world from my suburban existence at home.

My vivid memory of that scene includes my father whispering, “Stop scratching!” I would be scratching at my feet, first one, then the other, then back to the first. The sound bugged him. He wasn’t angry, just exasperated like someone being kept awake by an annoying, repetitious sound.

As a teenager, I went to the dermatology clinic once a year or so by myself (once I could drive) to renew my prescriptions for antibiotics that I needed to have on hand. One year, I asked if there was anything for itching, and they gave me an Ativan prescription. I discovered the way it stopped the itching was that it knocked me out. Okay, if I had 8 hours to sleep, but except for the weekends, which were festivals of sleep, I rarely had 8 hours.

Science is looking into it.

One night, I was driving home and listening to NPR, and I heard a doctor talking about a book he had just written about itching being a form of pain. (Itch and Pain: Similarities, Interactions, and Differences by Gil Yosipovitch (Author), Lars Arendt-Nielsen (Author), Hjalte Andersen (Author).)

My reaction to this was, “Well, yeah!” I didn’t seek out the book until the other day when I skimmed the free sample of the Kindle version. Boring! They did a lot of studies and found a lot of physical and psychological cross-overs between chronic pain and chronic itch.

Another time, a few years ago, I did my random and occasional Google search to see what might be new about EI. I stumbled upon this paper from Sweden, where a study looked at the quality of life of people of varying ages with EI. It included a discussion of how all-consuming the itching could be; this just in, the quality of life for people with EI sucks the big one.

I make light, but it is peculiar when you read that your quality of life is very poor for medical reasons. The medical condition that you’ve always had and still have. Just sayin’.

The report also confirmed many things I have discovered about dealing with my disability, more by trial and error than anything else. When you have something so rare (1 in 300k births) and non-fatal and dermatological, not a lot of mental time was ever spent on simple things to make life easier or more comfortable for someone like me. This lack of effort and failure of imagination resulted in much of the advice I was given for self-care being harmful or pointless.

Call in the locals.

Recently — 3 years ago? — my primary care doctor had the idea of trying Neurontin for the severe pain I occasionally get from blisters on my feet and lower legs. Opioids lessened the pain but were less than ideal for many reasons. The Neurontin worked for the pain (partly by knocking me out with a minimal dose). My doctor and I had reasoned that the nerves in/under my skin were inflamed when there were blisters. It was a shot in the dark, but it worked.

One night, it occurred to me that the itching also involved nerves, and I tried Neurontin for itching. It also worked for the itching, partly by knocking me out but also by just turning the dial down on the itching so I could fall asleep in the first place.

As I write this, my back is itching like crazy. But I don’t want to take anything for it because I won’t be clear enough to write.

But wait, there’s more!

Now that I am post-menopausal and 66, my skin is getting thinner, just as it does for “normal” skin. Except for me, when you add extreme itchiness, you get minor wounds and bleeding from relatively gentle scratching. So there’s that.

The itching is not in the top five worst things about my disability, but it does impact my quality of life. It is part of the “Hassle Factor,” about which I will write much more later.

These are the exact type of knitting needles I use to scratch my back.

Teri, I have no words of wisdom but am sitting here sending you love with all my might♥️ I am so grateful to have found an author who moves forward with such clarity, honesty, courage and vulnerability. You are such a gift.

I meditate regularly. I'm not sure if you are familiar with metta but know I am sending you deep metta🕉️🪷 and will hold you close in my heart, always 🙏

I’m in awe of you dealing with this through a lifetime, Teri. I’m sorry you’ve had to endure discomfort and lack of solutions and medical insight. My graddaughter has EDS/Erlers Danlos Syndrome which affects her mobility and connective tissue. Like you, she’s learned to own it, adapt and get on with life. My heart goes out to you; wishing you peace and hope that there’s a better treatment soon. Hugs.